The Pattern of Power Without Purpose

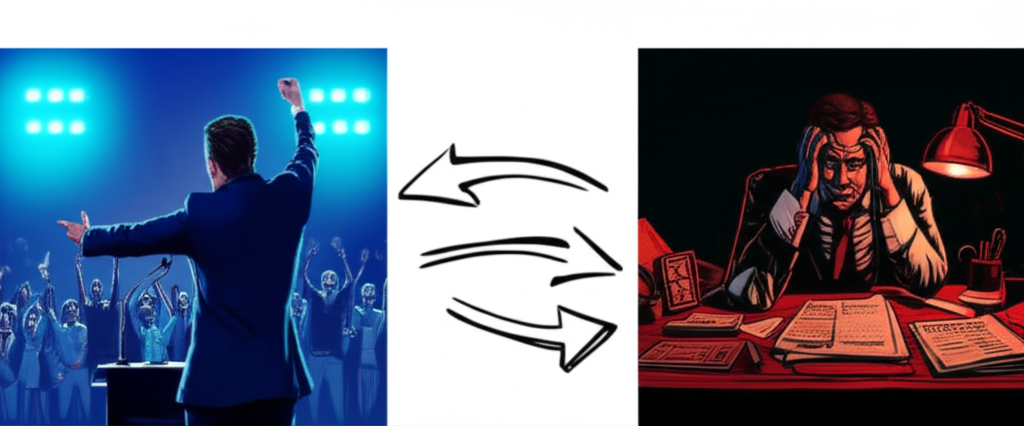

The Starmer government is the purest contemporary expression of a disease running through Western democracies: political systems that have evolved to select for people who are exceptionally good at winning power and catastrophically bad at using it. The skills that win elections — message discipline, opponent targeting, coalition assembly through ambiguity — are not just different from governing skills. They are often inversely correlated. The person who can say nothing offensive to anyone for four years is rarely the person with a vision strong enough to survive its first encounter with opposition.

Consider the policy reversals not as individual failures but as a pattern. The agricultural inheritance tax U-turn was not just politically damaging — it revealed there was never a coherent agricultural policy to U-turn from. The winter fuel payment cut was not a tough decision abandoned under pressure; it was a number plucked from a spreadsheet by people who had not modeled the political consequences because they had never built a political model that extended beyond the next election. When you reverse on everything, it becomes clear you were never going anywhere in particular.

This is the critique that Dominic Cummings has been making about Western governance for a decade, and Starmer has turned it into a case study. Governments staffed by media managers, party operators, and career politicians who have optimized for internal advancement rather than external delivery. People who can manage a headline cycle but cannot manage a procurement system. People who understand polls but not systems. The result is administrations that look competent in opposition — because opposition is a communications exercise — and collapse in government, because government is an execution exercise.

Reform UK polling above 30% is the measurable consequence. This is not a protest vote in any traditional sense. This is what happens when the vacuum of competence becomes so total that anyone who sounds like they have a plan — any plan, however sketchy — occupies the space. Nigel Farage does not need to be credible. He only needs to be standing while Starmer is falling.

The Johnson Template

The structural parallel to Boris Johnson's fall is instructive not because the scandals are identical but because the mechanism is. Johnson appointed Chris Pincher as Deputy Chief Whip despite multiple warnings about his conduct. The phrase "Pincher by name, pincher by nature" was attributed to Johnson himself. When the inevitable happened and Pincher was accused of groping two men at a private members' club, Johnson's first instinct was to deny knowledge of prior complaints. The cover-up compounded the original error, and 62 of 179 government figures resigned in 48 hours.

Starmer's appointment of Mandelson follows the same logic of political utility overriding known risk. But it adds a layer that Johnson's case lacked: this is the same man, caught the same way, twice before. Mandelson's "adoration of wealth and power," as the New Statesman put it, was not a hidden character trait. It was the defining feature of a thirty-year career in public life. Starmer had the 1998 resignation, the 2001 resignation, and the publicly known Epstein connections — and still concluded the political utility was worth it.

The deeper pattern is about a specific failure mode in political leadership: confusing loyalty with judgment. Blair's loyalty to Mandelson was rooted in genuine political debt — Mandelson engineered New Labour. Johnson's loyalty to Pincher was transactional — he needed a whip enforcer. Starmer's calculation appears to have been something more fragile still: the belief that he needed Mandelson's strategic mind badly enough to ignore the man's extraordinary talent for self-destruction. Three leaders, three calculations that the upside of a compromised ally outweighed the downside, three incorrect answers.

The Coordination Problem

So does this mean Starmer's days are numbered? Removing a sitting Prime Minister is a coordination problem before it is a political one. Nobody wants to be the first mover. The regicidal figure in British politics — the one who wields the knife — rarely inherits the crown. Geoffrey Howe destroyed Thatcher but did not replace her. The MPs who moved against Johnson waited until the cascade was already underway before declaring. First-mover disadvantage is real and well-understood by anyone who has survived in Westminster long enough to know the rules.

For Labour, the structural barriers are even higher. Triggering a leadership challenge requires 81 of 405 MPs — a 20% threshold that is harder to reach than the Conservative equivalent. No Labour Prime Minister has ever been challenged mid-term by their own party. The cultural resistance to regicide is stronger on the left, where solidarity is not just a tactic but a tribal identity. Gordon Brown survived from 2008 to 2010 with comparable polling numbers because Labour MPs genuinely did not know how to execute a mid-term removal. The plotters always blinked.

But prediction markets are pricing in an exit. Polymarket, with over $4 million in volume, puts the probability of Starmer leaving by June at 68%. Eurasia Group estimates an 80% chance he is gone within the year. The May local elections function as the Schelling point — the moment where coordination becomes possible because everyone is looking at the same results at the same time. If Labour loses councils in the catastrophic fashion the MRP models suggest, the 81-MP threshold stops being a barrier and starts being a formality. "The voters have spoken" is a sentence that solves the first-mover problem.

The Stakeholder Trap

Here is where the analysis gets uncomfortable for those expecting a clean resolution. The bond market is watching, and the bond market has its own preferences. Gilt yields are at 4.6%, the highest since October, and every institutional investor holding UK government debt is running the same calculation: Starmer is weak, but what comes next? A Labour leadership contest that elevates a candidate to the left of Starmer — which is where most of the parliamentary party sits — could spook the gilt market further. The paradox is that the financial argument for removing Starmer collapses if his replacement is someone the markets fear more.

The succession problem is genuine. Angela Rayner carries a tax investigation that would dominate any leadership campaign. Wes Streeting has Mandelson ties of his own. There is no clean challenger waiting in the wings with a mandate, a coalition, and a story to tell. This creates a Mexican standoff: everyone has reasons to move and everyone has reasons to wait. The person who would benefit most from Starmer's departure cannot be identified, which means the coordination problem remains unsolved even if the motivation is overwhelming.

Meanwhile, the threat that should dominate Labour's strategic thinking is barely discussed in the leadership drama: Reform UK is polling above 30% and, under some MRP models, is projected to win 381 seats at the next election. Every day Labour spends on internal psychodrama is a day Reform consolidates its position as the default vehicle for anti-establishment sentiment. The irony is that Labour won its massive majority not because voters loved Starmer but because the right was split between the Conservatives and Reform. That splitting could easily reverse, with Labour and the Liberal Democrats dividing the centre-left vote while Reform hoovers up the rest.

The Contrarian Read

The scariest outcome is not dramatic collapse. It is indefinite paralysis. A government too weak to govern, too embedded to remove, stumbling forward on institutional inertia while the country's problems compound.

The succession paradox is not a temporary condition. It is a feature of a party that spent a decade in opposition fighting itself rather than developing a governing bench. Strong gilt auctions remain oversubscribed, which suggests the bond market's bark may be worse than its bite. And Labour's institutional antibodies — the tribal loyalty, the horror of public fratricide, the memory of the Corbyn wars — may prevent the immune response from firing even when the diagnosis is terminal.

The zombie government scenario has historical precedent and structural support. Starmer does not need to be good. He needs the alternative to be worse, or at least uncertain enough that risk-averse MPs choose the devil they know. And a 174-seat majority provides an enormous buffer — even losing a hundred seats at the next election would leave Labour in government.

What to Watch

May's local elections are the inflection point. Three criteria would signal genuine collapse rather than zombie government: ten or more Labour MPs publicly calling for Starmer's resignation, which would indicate the coordination problem is solving itself; gilt yields breaching 5%, which would dissolve the financial argument for keeping a weak but predictable leader; and a clean challenger emerging with union backing, which would provide the institutional infrastructure for a leadership contest.

The smart money says Starmer goes. The structural analysis says: probably, but later and messier than anyone expects. Western democracies have gotten very good at selecting leaders who can win power and very bad at removing them when they cannot use it. The trap is not Starmer's alone. It belongs to every political system that has optimized for the campaign and forgotten about the country that comes after.