The Walkman Trap: Why China's Tech Bet Is Japan's Lost Decade All Over Again

Japan didn't fail because its leaders were incompetent—they failed because they doubled down on industrial policy while trapped under America's security umbrella. China is making the same bet, but without the same constraints.

“Japan's leaders weren't incompetent—they were constrained. And the constraint that mattered most wasn't economic or cultural. It was strategic.”

The conventional story of Japan's Lost Decade is one of domestic failure: a bubble inflated by reckless monetary policy, zombie banks kept alive by cowardly regulators, and a cultural inability to embrace creative destruction. But this narrative misses something crucial. Japan's leaders weren't incompetent—they were constrained. And the constraint that mattered most wasn't economic or cultural. It was strategic. Japan lived under America's security umbrella, which meant when Washington demanded currency appreciation, market opening, and industrial restructuring simultaneously, Tokyo had to comply. China's leaders have spent three decades studying this playbook. The question is whether they've learned the right lessons—or whether they're walking into the same trap with their eyes wide open.

The Walkman Trap: Why China's Tech Bet Is Japan's Lost Decade All Over Again

Japan didn't fail because its leaders were incompetent—they failed because they doubled down on industrial policy while trapped under America's security umbrella. China is making the same bet, but without the same constraints.

On October 1, 1982, Sony's chairman Akio Morita stood in a Manhattan hotel ballroom and watched American executives pass around his company's newest creation like a curiosity from another planet. The CDP-101, the world's first commercial compact disc player, represented everything American industry feared about Japan: flawless manufacturing, relentless miniaturization, and the audacity to obsolete an entire Western technology stack overnight.

Morita had reason to feel triumphant. Japanese companies had already conquered televisions, cameras, and motorcycles. The Walkman had become a global phenomenon. Now Sony and its peers were moving up the value chain into semiconductors, computers, and telecommunications equipment. American CEOs whispered nervously about Japan as 'the land of the rising sun'—emphasis on rising.

Eight years later, Morita would publish a provocative essay titled 'A Japan That Can Say No,' arguing his country should stop deferring to American interests. The book became a sensation in both countries—and a warning shot that Washington heard clearly. Within months, American trade negotiators would begin a coordinated campaign that would reshape the Japanese economy for a generation.

What happened next should sound familiar. A rising industrial power, flush with technological success and trade surpluses, faces coordinated pressure from the global hegemon. Its leaders respond by doubling down on state-directed investment in strategic industries. Asset prices soar, then collapse. And then comes the long, grinding deflation that turns triumph into stagnation.

This is not ancient history. This is the script playing out in Beijing right now.

The conventional story of Japan's Lost Decade is one of domestic failure: a bubble inflated by reckless monetary policy, zombie banks kept alive by cowardly regulators, and a cultural inability to embrace creative destruction. But this narrative misses something crucial. Japan's leaders weren't incompetent—they were constrained. And the constraint that mattered most wasn't economic or cultural. It was strategic. Japan lived under America's security umbrella, which meant when Washington demanded currency appreciation, market opening, and industrial restructuring simultaneously, Tokyo had to comply. China's leaders have spent three decades studying this playbook. The question is whether they've learned the right lessons—or whether they're walking into the same trap with their eyes wide open.

The Zombie Myth

Every economics textbook tells the same story about Japan's Lost Decade: regulators failed to close insolvent banks, creating 'zombies' that starved healthy firms of credit while keeping failing companies on life support. The solution was obvious—do what America did during the S&L crisis and rip off the bandaid.

There's just one problem with this narrative. Japan literally couldn't do what America did. Until 1998, Japanese law contained no mechanism for resolving failed banks. The Deposit Insurance Corporation had no authority to take over institutions. There was no legal framework for wiping out shareholders or forcing mergers. When American critics demanded Japan 'just restructure,' they were demanding something that required legislation that didn't exist.

This wasn't an oversight. Japan's postwar financial system was designed for a different purpose: channeling savings into industrial development through stable, long-term bank relationships. The absence of resolution authority wasn't a bug—it was a feature of a system that prioritized stability over efficiency. By the time the bubble burst in 1991, changing this system required not just political will but constitutional navigation through a system designed for consensus, not crisis response.

The Bank of Japan faced its own constraints. Until the BOJ Act revision of 1998, the central bank required Ministry of Finance approval for rate changes. The institution America kept telling to 'act independently' legally could not act independently. Every criticism of BOJ passivity ignored this fundamental structural reality.

The Players and Their Traps

Understanding Japan's Lost Decade requires mapping who had skin in the game—and what trapped each player.

The US Treasury and Trade Representative faced a genuine dilemma. Japanese trade surpluses were politically toxic in Congress, where protectionist sentiment threatened to boil over. But Japan was also America's most important Pacific ally, host to critical military bases, and a bulwark against Soviet expansion. Push too hard and you destabilize the alliance. Push too softly and you lose Congress.

Japan's Ministry of Finance was caught between two imperatives: maintaining financial stability and preserving strategic autonomy. MOF officials understood the banking problems better than their American critics realized—internal documents show clear-eyed assessments of bad loan exposure. But they also understood that rapid restructuring would require accepting American demands that went far beyond banking: opening markets, appreciating the yen, and effectively surrendering industrial policy.

Regional banks and credit cooperatives faced extinction. Their business model depended on long-term relationships with local firms, many of which were now technically insolvent. The cross-shareholding networks that had enabled Japan's industrial rise now prevented market-based restructuring. Selling distressed assets meant selling them to foreign vulture funds—politically unacceptable and economically destabilizing for regional economies.

The construction and real estate lobbies wielded disproportionate political power through their alliance with the Liberal Democratic Party. They needed government infrastructure spending and stable land prices to survive. This created a doom loop: fiscal stimulus flowed to construction, which prevented land price adjustment, which prolonged the banking crisis, which required more fiscal stimulus.

Behind everything sat a structural reality that constrained all other players: Japan's security dependence on the United States meant that when American pressure campaigns demanded compliance, Japan had limited room to refuse.

The Plaza Accord's Long Shadow

The conventional timeline places Japan's crisis beginning in 1991 with the bubble's collapse. The real story starts six years earlier, in September 1985, at the Plaza Hotel in New York.

The Plaza Accord forced Japan to accept dramatic yen appreciation—from 240 yen per dollar to 120 within two years. This was economic shock therapy delivered to an ally. Japanese exporters suddenly faced 50% cost increases in dollar terms.

Japan's response was rational given its constraints. Unable to resist American currency demands and unwilling to accept immediate industrial collapse, policymakers chose to inflate domestic demand. The Bank of Japan cut rates to 2.5%. The Ministry of Finance loosened lending restrictions. The explicit goal was to offset export sector losses with domestic asset appreciation.

It worked—too well. Land prices in major cities tripled. Stock prices quadrupled. Japanese companies went on a global buying spree, from Rockefeller Center to Columbia Pictures. American commentators warned of Japanese economic conquest, missing entirely that this buying spree was a symptom of distorted domestic prices, not industrial strength.

When the bubble popped, Japan faced a choice: rapid restructuring that would validate American criticism and require even more concessions, or gradual adjustment that preserved institutional autonomy but risked prolonged stagnation. Regulators chose gradual adjustment—not from incompetence, but from strategic calculation.

The tragedy is that both choices led to the same destination. Rapid restructuring would have required American capital and American-style corporate governance. Gradual adjustment produced a decade of deflation. Either way, Japan's industrial challenge to American dominance ended.

MITI's Ghost

In 1982, Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry announced the Fifth Generation Computer Project—a moonshot to leapfrog American dominance in computing through government-directed investment in artificial intelligence and parallel processing. The project would receive hundreds of millions of dollars and coordinate Japan's top technology companies toward a common goal.

A decade later, the project was quietly wound down. Its main achievements were incremental improvements in existing technologies, not the revolutionary leap promised. American computer companies, driven by market competition and venture capital, had lapped their Japanese rivals in software, networking, and eventually hardware design.

This pattern—government-directed investment in strategic sectors, initial impressive gains, followed by stagnation as market-driven rivals adapt—repeated across Japanese industrial policy. Semiconductors, aerospace, biotechnology: in each case, MITI's ability to coordinate investment proved weaker than America's decentralized innovation system.

The lesson Japanese policymakers took from this experience was not that industrial policy fails, but that it requires better execution. They doubled down on coordination, on picking winners, on channeling resources to strategic sectors. This was the mindset they brought to the post-bubble recovery: if Japanese industry faced American pressure, the solution was more strategic investment, not market liberalization.

China's leaders have studied this history carefully. Their conclusion? MITI failed not because industrial policy is flawed, but because Japan was constrained by American strategic dependence. A truly sovereign industrial power, they reason, could execute the same playbook with better results.

The Deflation Trap Has No Exit

Here is what the conventional narrative completely misses: Japan's Lost Decade was not a policy failure that better choices could have prevented. It was the inevitable result of a rising industrial power challenging the hegemon while dependent on that hegemon for security.

Once the Plaza Accord forced yen appreciation, Japan had only bad options. Accepting immediate industrial decline was politically impossible. Inflating domestic assets created the bubble. Deflating the bubble without resolution tools created zombies. Restructuring with American capital meant surrendering industrial autonomy. Every path led to lost decades.

The binding constraint wasn't the missing bank resolution law, though that was critical. The binding constraint was strategic dependence. Japan could not say no to American demands because American security guarantees underwrote Japan's entire postwar order. When Washington pushed, Tokyo had to accommodate.

China's leaders understand this. Their entire strategic posture for thirty years has been designed to avoid Japan's trap: building independent military capabilities, developing domestic technology supply chains, accumulating financial reserves, and maintaining state control over capital flows. They watched Japan subordinate economic sovereignty to alliance politics and concluded that sovereignty must come first.

But they may have learned the wrong lesson. Avoiding strategic dependence doesn't solve the deflation problem—it just removes one constraint while leaving others intact.

BYD and the Trap That Waits

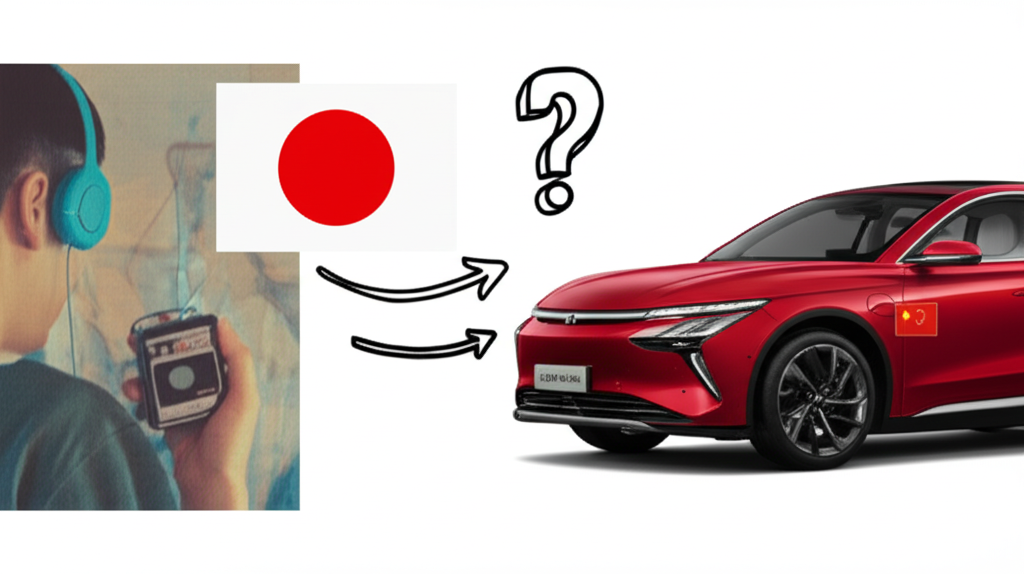

In 2024, BYD surpassed Tesla as the world's largest electric vehicle manufacturer. Chinese companies dominate solar panel production, battery manufacturing, and increasingly, advanced semiconductors. The echoes of 1982 Sony are unmistakable. A rising industrial power masters manufacturing, moves up the value chain, and begins displacing Western competitors in strategic technologies.

China faces the same coordinated pressure Japan faced: trade restrictions, technology controls, currency manipulation accusations, and demands for market opening. But unlike Japan, China can say no. It has nuclear weapons, a seat on the UN Security Council, and no American troops on its soil. The strategic constraint that bound Japan does not bind China.

This should change everything. Without the need to defer to Washington, China could pursue aggressive restructuring, accept short-term pain, and emerge stronger. Instead, China is making the same choice Japan made: doubling down on state-directed investment in strategic sectors while avoiding the consumption rebalancing that might break the deflation cycle.

The property sector is China's bubble. Evergrande and Country Garden are its zombie banks. The Belt and Road Initiative is its MITI moonshot. And the deflationary pressures are identical: aging demographics, debt overhang, asset price declines, and the demand shortfall that comes when investment-led growth exhausts its runway.

China's leaders are materialists in the Marxist sense—they believe in production, industry, tangible output. The idea of shifting resources toward consumption, services, and domestic demand strikes at their ideological core. Japan's leaders faced a similar cultural obstacle: the salaryman ethic of production and export was not easily redirected toward leisure and consumption.

The difference is that Japan eventually acquiesced to American pressure and began the long, painful rebalancing that its alliance required. China has no such external force compelling adjustment. It can continue the investment-led, production-focused, export-driven model indefinitely—or at least until the internal contradictions become impossible to ignore.

This is the darkest possibility: that China's freedom from American strategic constraint enables it to avoid the adjustments that might, eventually, break the deflationary spiral. Japan's Lost Decade ended, eventually, with structural reforms forced by crisis. China's could last longer precisely because no external power can force change.

The Walkman gave way to the iPod. Sony's technological leadership was a way station, not a destination. BYD may follow the same path—or it may not. But the underlying pattern remains: state-directed investment in strategic sectors, impressive initial results, and the long grinding deflation that comes when a development model exhausts its potential and the political system cannot pivot.

China has studied Japan's failure. It has removed the strategic constraint that bound Tokyo to Washington's demands. But it has not removed the economic logic that made Japan's Lost Decade inevitable. It has merely bought itself the freedom to make the same mistakes for longer.

The Pattern: Rising industrial powers that challenge hegemonic economic leadership face coordinated pressure that forces either strategic subordination or prolonged stagnation—and state-directed investment makes the stagnation worse, not better.

Modern Application: China's massive reinvestment in advanced technology sectors mirrors MITI's failed moonshots; without external pressure forcing consumption rebalancing, China may experience longer stagnation than Japan precisely because it can sustain the investment-led model beyond its productive potential.

The Pattern

China's massive reinvestment in advanced technology sectors mirrors MITI's failed moonshots; without external pressure forcing consumption rebalancing, China may experience longer stagnation than Japan precisely because it can sustain the investment-led model beyond its productive potential.

Deep Dive Analysis

All Stakeholders

Japanese Ministry of Finance

Maintain financial system stability and regulatory authority while preserving Japan's strategic autonomy within US alliance framework

Legal framework for bank resolution didn't exist until 1998

Why limiting: Could only liquidate or bail out banks - no middle path for orderly restructuring

Career incentives favored forbearance over aggressive intervention

Promoted expertise and control while lacking legal tools to act decisively

Regional banks and credit cooperatives

Survival through maintaining local lending relationships and avoiding merger/closure during economic restructuring

Cross-shareholding networks preventing market-based restructuring

Why limiting: 65% of equity locked in mutual holdings made independent action impossible

LDP connections through local constituencies

Promoted local relationship banking while being structurally trapped in zombie lending

Bank of Japan under MOF oversight

Balance domestic economic needs with international monetary cooperation requirements while gaining institutional independence

Lacked formal independence until 1998 BOJ Act revision - required MOF approval for rate changes

Why limiting: Could not implement independent monetary policy during critical crisis period

G7 commitments limiting competitive devaluation options

Promoted technical monetary expertise while being institutionally subordinated

US semiconductor and computer industry

Prevent Japanese dominance in next-generation computing and maintain US technological leadership

Japanese companies had technological and cost advantages in key components

Why limiting: Required government intervention to compete effectively

Window closing for establishing semiconductor dominance

Promoted free market competition while lobbying for export controls and trade restrictions

US Treasury and Trade Representative

Needed to reduce Japan's trade surplus without destroying strategic alliance or creating regional instability that could benefit Soviet Union/China

Domestic protectionist pressure conflicting with strategic alliance needs

Why limiting: Had to manage domestic industry complaints while preserving Japan as critical Cold War ally

Regional security environment required stable Japan

Promoted 'market-driven rebalancing' narrative while orchestrating coordinated pressure campaign

Construction and real estate lobbies

Maximize government infrastructure spending and maintain land values during economic transition

Dependence on LDP political protection and MOF credit allocation

Why limiting: Required continued political support for public works spending

Basel I capital requirements forcing bank asset concentration in real estate

Promoted economic stimulus through infrastructure while being core zombie sector

Chat with this story

Sign in to unlock AI-powered exploration

For people who'd rather understand than react.

More Deep Dives

The Script That Always Plays Out: Why America's Immigration Enforcement Crises Follow the Same Pattern Every 70 Years

Federal enforcement promises, capacity constraints, selective crackdowns, local resistance where economically viable—the cycle repeats because the underlying incentives never change.

January 21, 2026

Is Protein the New Low-Fat? The $45B Marketing Question

Americans already overconsume protein by 20%, yet the food industry built a multi-billion dollar market anyway. History suggests we've seen this script before.

January 21, 2026

The Government Strikes Back: How Communications Technology and Economic Stress Reshape Politics

From 1848 to 2026: when new communications tech meets economic anxiety, government reasserts itself. Both left and right populism lead to the same destination.

January 18, 2026

Bread and Circuses 2.0: What Rome Teaches Us About a Post-Work Economy

Rome managed mass non-employment for 600 years. If AI takes the jobs, what can we learn from history's one successful experiment?

January 17, 2026